Imperative Mood (Imperative)

Look, this really isn’t difficult. Commands ( orders, mandates) using the imperative mood. Also known as the imperative, from imperare = to command. With this повелительное наклонение, you can also be polite: it can express a wish, request, or advice.

You need to know a few things to be able to do this in Russian.

Take a look.

они-form

To form the imperative mood in Russian, you start with the они (they) conjugation of the verb. Remove the ending and replace it with something else.

For example, -и or -ите. In сказать (to say, to tell), the conjugation (они скажут) provides the stem (скаж-) which leads to скажи (informal) and скажите (formal or plural) as the imperative. This immediately shows why you shouldn’t rely on the stem of the infinitive.

й, и or ь

There are three different endings for forming the imperative mood. Or actually six, since each has an informal and a formal (or plural) version.

-й, -йте

The stem ends in a vowel. думать (to think): они думают makes дума- the stem. Imperative: думай, думайте. Think positive:

думай позитивно. Do (делать) good:

делай добро.

-и, -ите

The stem ends in a consonant, and the stress in the я-form is on the last syllable. In the example of сказать: those скажи and скажите are also due to я скажу́.

In помнить (to remember) and молчать (to be silent), you get the same endings (помни, помните and молчи, молчите) because of the two consonants at the end in помн- (from они помнят) and молч- (from они молчат).

-ь, -ьте

Also in

быть (to be), the stem ends in a consonant (буд-, from они будут), but the stress in я бу́ду gives us будь and будьте. Будь здоров, be healthy. Будьте любезны, be kind, and вежливы, polite.

This is also the case with other verbs, such as ответить and готовить: imperative forms ответь, ответьте and готовь, готовьте, due to я отве́чу and я гото́влю.

Exceptions

Verbs with an irregular imperative form include есть (ешь, ешьте), лечь (ляг, лягте), and пить (пей, пейте).

Also дать and давать. You often hear дай or дайте (give, please give), and давай (or давайте). See 10 ways to use Давай in Russian (Hack Your Russian, 2021, 23 mins) and Давай(те): Suggestions & Invitations with Let’s (Amazing Russian, 2017, 14 mins).

Don’t do

The imperative is often seen in combination with не (don’t, no). The command then becomes a prohibition, or negative advice. The verbs in these constructions are always imperfective.

Don’t smoke, don’t drink: не кури, не пей (не курите, не пейте). Thou shalt not kill, commit adultery, or steal (Exodus/Исход 20:13-15): Не убивай, Не нарушай супружескую верность, Не кради. Remember that now.

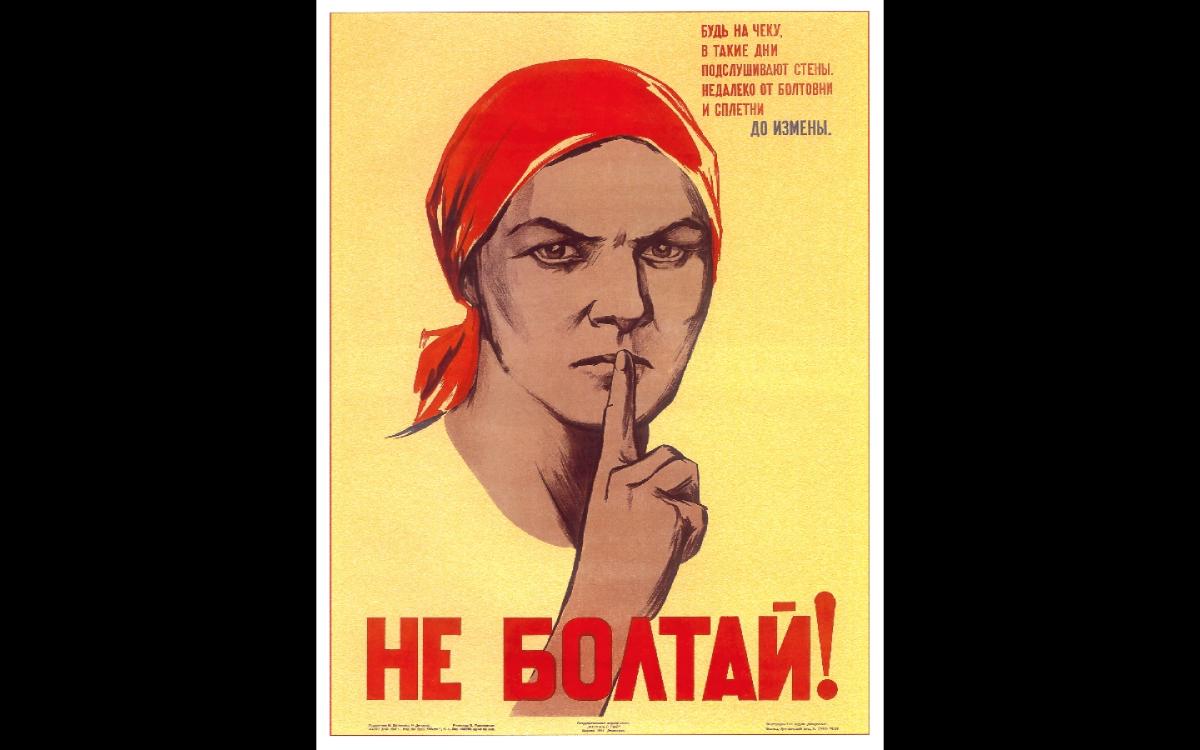

A famous example is не болтай, a Russian version of Loose lips sink ships. Don’t chatter, no unnecessary talk. From the verb болтать (also seen in Болтать – врагу помогать, chatter helps the enemy). Poster from 1941, by Нина Ватолина (1915–2002) and Николай Денисов (1917–1982).

Imperative mood in Russian. How to form it

(Ru-Land Club, 2020, 12 mins)

From the same channel: Imperative mood in Russian. Повелительное наклонение глагола в русском языке (2017, 17 mins).

How to Give Commands and Requests | Russian Language

(Be Fluent in Russian, 2018, 7 mins)

Russian Imperatives (I): Vowel stems

(Russian grammar, 2017, 2 mins)

Then watch:

- Imperatives (IIa): Consonant Stems (2017, 2 mins)

- Imperatives (IIb): Consonant Stems (2017, 2 mins)

- Imperatives (III): A Few Exceptions (2017, 3 mins)

The Imperative: Forms and Aspects

(Amazing Russian, 2017, 14 mins)

More

See:

- Forming Russian Imperatives (Russian Through Propaganda, 2020, 52 mins), also see More on the Russian Imperative (2020, 54 mins) and Reviewing Imperatives, with Aspect (2020, 37 mins)

- Aspect in the Imperative (Elena Clark, 2020, 14 mins)

- Imperative mood in Russian (Russian Connection, 2020, 6 mins)

- Russian through music: Imperatives (Learn Russian With Alfia, 2019, 10 mins)

- Imperative Mood of Russian Verbs (Learn Russian with Irina, 2019, 4 mins)

- Imperatives (Intermediate Russian, 2019, 4 mins)

- Russian language. Imperative form (Naya Polo, 2019, 7 mins)

- Russian Grammar: Imperative form (Rus 4U, 2017, 5 mins)

- Russian imperative mood, повелительное наклонение (Antonia Romaker, 2015, 11 mins), also a part 2

- Let’s speak Russian – Imperative mood in Russian language (RussianASL, 2015, 5 mins)

- Imperative in Russian – how to form commands (Anuta Klein, 2012, 1 min)

See/read:

- Commands – the Imperative Mood (The Russian Blog, 2018)

- Command Forms Beyond the Imperative in Russian (Russian Language Blog, 2018)

- Imperative forms (Learn Russian/RT)

- Imperative Mood: Commands, Advice, Invitations (RussianDict)

- Russian Imperative mood (Learn Russian Step by Step)

- Subjunctive and Imperative Mood (Master Russian)

- The Imperative mood (Linguapedia)

More