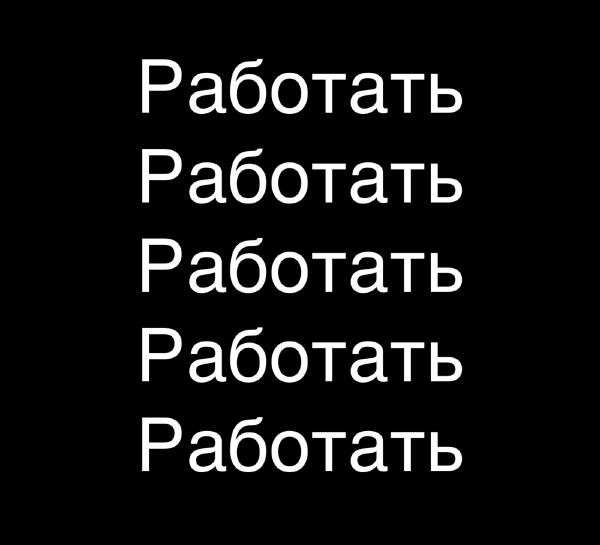

VERBS

Language

Verbs work for those who want to make sentences. There - work and make, there you already have two. And try to make Russian out of that sentence if you if you don’t know работать or делать. So work, also on your vocabulary.

SIXTH NOUN: LOCATIVE/PREPOSITIONAL

Language

The sixth noun, in Russian предложный падеж, is for most students the first one they learn. The reason is simple: the sixth grammatical case itself is.

Perfective and imperfective

Language

This often comes as a setback for students of Russian: of (almost) every Russian verb there are two. Which do mean approximately the same thing, but express very different things. So you need to know both, and of both learn the conjugations.

Imperative Mood (Imperative)

Language

Look, this really isn’t difficult. Commands (

orders, mandates) using the

imperative mood. Also known as the imperative, from imperare = to command. With this повелительное наклонение, you can also be polite: it can express a wish, request, or advice.

Fifth Case: Instrumental

Language

With “with,” you immediately have the key word for the instrumental case. With a discount, with Katya, with respect, by hand: all instrumental case or творительный падеж. You can do much more with this case; it’s truly a beautiful and useful tool.

ш and щ: Spot the Differences

Language

One looks like a “w” with straight lines (like an E that has fallen over), and the other is similar but with a tail or hook. Or something like that. Not only do ш and щ look similar, but their sounds are also close. So close that distinguishing them isn’t easy.

Russian Adjectives (Прилагательные)

Language

Useful, convenient, interesting: adjectives are everywhere and unavoidable. So it is sensible, rewarding, fascinating, attractive, necessary, etc., to be able to use them in speech and writing. Two things are needed for that.

Fourth Case: Accusative

Language

The joker in a card game, the knight in chess: if you’re looking for something as quirky among the six cases, you’ll quickly land on the fourth. Rules for the

accusative or винительный падеж are simple, yet (or perhaps because of that) it can easily catch you off guard.

What kind of times do we live in? It’s a question one might ask these days. To get an answer in Russian (or to distract yourself from the times), let’s start by learning the names of the months and days. Here they are gathered together, with a bonus of some etymology and grammar thrown in.

Third Case: Dative

Language

The

dative case in Russian is called дательный падеж. The name itself gives you a clue when to use it. In дательный, you find дать, which means “to give” (also давать—see

here for conjugations). This originates from Latin, where dare means “to give” and datum means “given.” In Russian, when something is given, it’s done in the dative case, just like in many other languages.

A Russian name consists of three parts: a first name (имя), a patronymic or father’s name (отчество), and a last or family name (фамилия). The abbreviation Ф.И.О. (фамилия, имя, отчество) is well-known to Russians and appears on their passports, driver’s licenses, and related documents.

The nominative case (именительный падеж) is almost a freebie in Russian. The way a word appears in the dictionary is how it appears in the nominative case. ‘Nominative’ comes from

nominare (to name), and in

именительный you may recognize имя, meaning name.

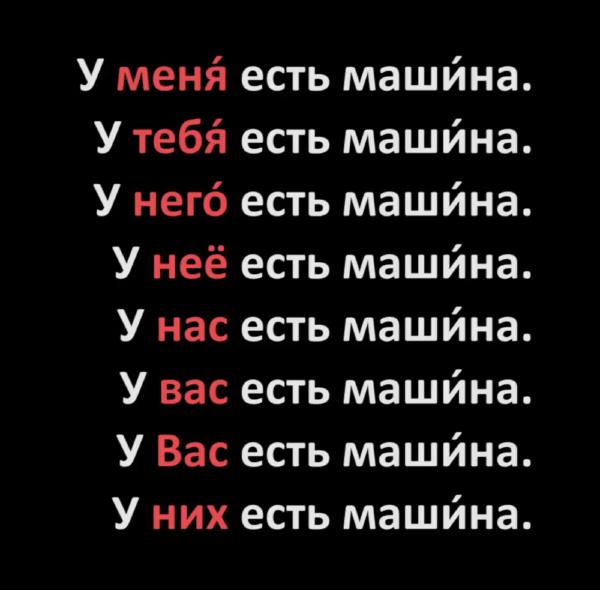

Personal Pronouns

Language

You quickly learn or might already know the ‘regular’ forms of the Russian personal pronouns (those in the nominative case). I = я, you = ты, he = он, she = она, it = оно, we = мы, you (formal/plural) = вы, and they = они. These words change depending on the case; however, there are many similarities within these changes.

To have, to have, to have

Language

Knowledge you want to have: the verb ‘to have’ technically doesn’t exist in Russian. Of course, there are ways to express possession, but it’s done a bit differently than in many other languages. Somewhat indirectly. Less possessive. Or: a bit more lyrical.

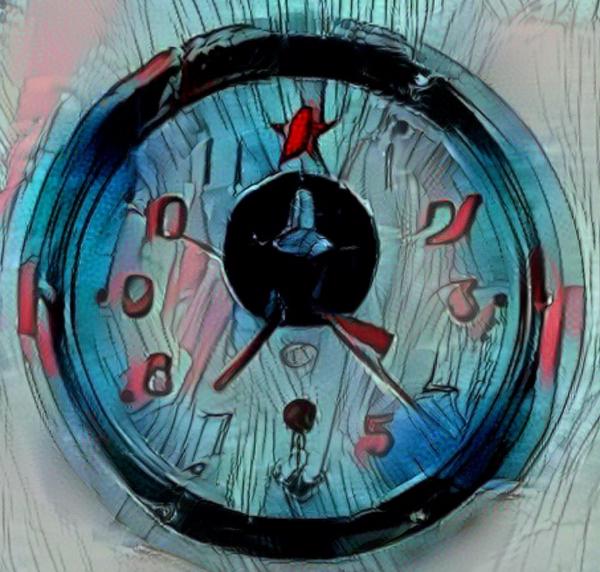

Telling Time in Russian

Language

When Russians tell time, they look ahead. In the first half-hour, they are already on their way to the next, and in the second, they tell you how far it is to the next hour. To understand this and be able to do it yourself, there are a few things you need to know. Here are the most important ones.

First and Second Conjugation

Language

Many Russian verbs end in -ать or -ить. Both categories have their own conjugations. Verbs ending in -ать follow the first or е/ё conjugation; if they end in -ить, then the second or и conjugation applies (exceptions and irregularities aside).

Why Learn Russian?

Language

There are many reasons to (want to, start, or continue) learning Russian. It’s the language of the world’s largest country, the biggest language in Europe, and it’s useful in many countries outside of Russia too. And perhaps the best reason to learn Russian: simply the most beautiful language of all.

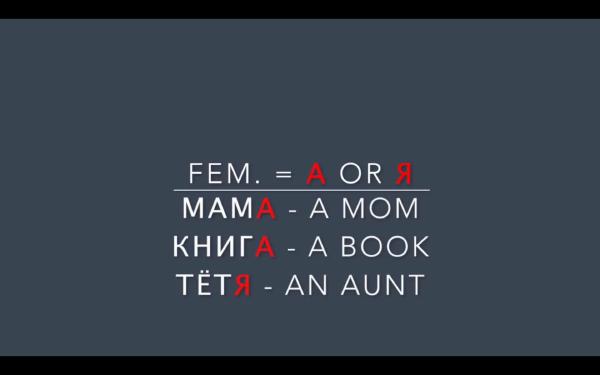

Masculine, Feminine, Neuter

Language

Every noun in Russian is masculine, feminine, or neuter. You always need to know which category it falls into, and usually, that’s not difficult. Words ending in a consonant are masculine, words ending in а or я are feminine, and words ending in о or е are neuter.

Gluing Sounds

Language

Russian is a phonetic language. The way you pronounce words is how you write them. The way they are written tells you how to pronounce them. Each letter has its own sound and generally keeps it. Unlike Dutch and English, Russian is quite consistent in this regard.

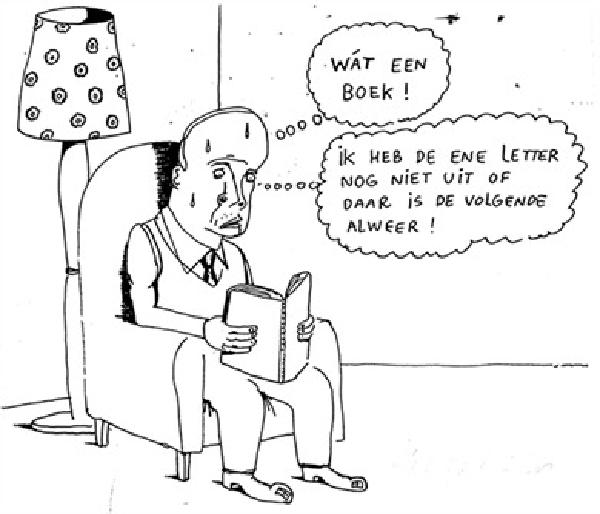

(Image © Gummbah)

(Image © Gummbah)

Vocabulary

Language

A short poem (called ‘Woordenschat’ – Vocabulary) by Jaap van Lakerveld goes like this:

A man whose small vocabulary

I estimate to be six words

says to the woman who loves him

when she asks how he feels about her

‘I don’t have the words, my dear’

A man whose small vocabulary

I estimate to be six words

says to the woman who loves him

when she asks how he feels about her

‘I don’t have the words, my dear’