SIXTH NOUN: LOCATIVE/PREPOSITIONAL

Language

The sixth noun, in Russian предложный падеж, is for most students the first one they learn. The reason is simple: the sixth grammatical case itself is.

Perfective and imperfective

Language

This often comes as a setback for students of Russian: of (almost) every Russian verb there are two. Which do mean approximately the same thing, but express very different things. So you need to know both, and of both learn the conjugations.

To emphasize one more time that - and why - it is useful and important to to know where the

emphasis added in Russian falls. And how that knowledge helps you, in both the spelling of the word крокодил (crocodile) and the pronunciation of names such as Tolstoy.

Imperative Mood (Imperative)

Language

Look, this really isn’t difficult. Commands (

orders, mandates) using the

imperative mood. Also known as the imperative, from imperare = to command. With this повелительное наклонение, you can also be polite: it can express a wish, request, or advice.

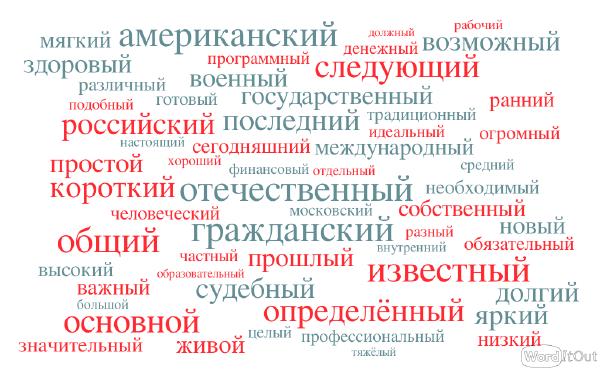

Russian Adjectives (Прилагательные)

Language

Useful, convenient, interesting: adjectives are everywhere and unavoidable. So it is sensible, rewarding, fascinating, attractive, necessary, etc., to be able to use them in speech and writing. Two things are needed for that.

Russian Ordinal Numbers

Language

After covering the basic

numbers or

cardinal numbers, here’s the second part:

ordinal numbers, like first and second. In English, they’re called ordinal numbers, and in Russian, they are порядковые числительные (stress on the second syllable both times). Ordinal numbers are usually easy to derive from the cardinal number – although words like “first” and “second” are exceptions right from the start.

Fourth Case: Accusative

Language

The joker in a card game, the knight in chess: if you’re looking for something as quirky among the six cases, you’ll quickly land on the fourth. Rules for the

accusative or винительный падеж are simple, yet (or perhaps because of that) it can easily catch you off guard.

Third Case: Dative

Language

The

dative case in Russian is called дательный падеж. The name itself gives you a clue when to use it. In дательный, you find дать, which means “to give” (also давать—see

here for conjugations). This originates from Latin, where dare means “to give” and datum means “given.” In Russian, when something is given, it’s done in the dative case, just like in many other languages.

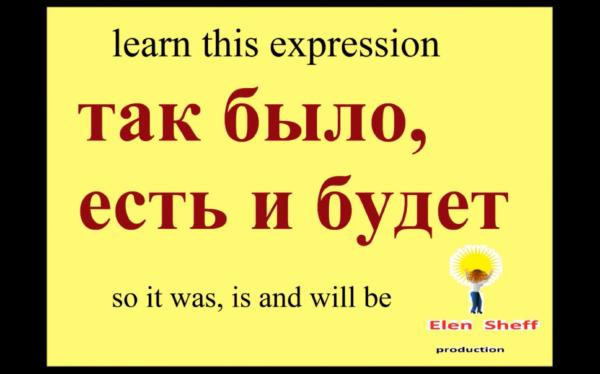

To Be or Not to Be

Language

Just like with

the verb “to have”, there’s something odd about the verb “to be” in Russian. It does exist—it’s called быть—but it often goes missing in sentences, unless you’re speaking in the past or future tense. In the present tense, it’s frequently omitted.

Second Case: Genitive

Language

As easy as it was with the

first case, it becomes that much more complicated with the second. The genitive or родительный падеж is challenging in several areas. It is the most used and versatile, but also the most complex.

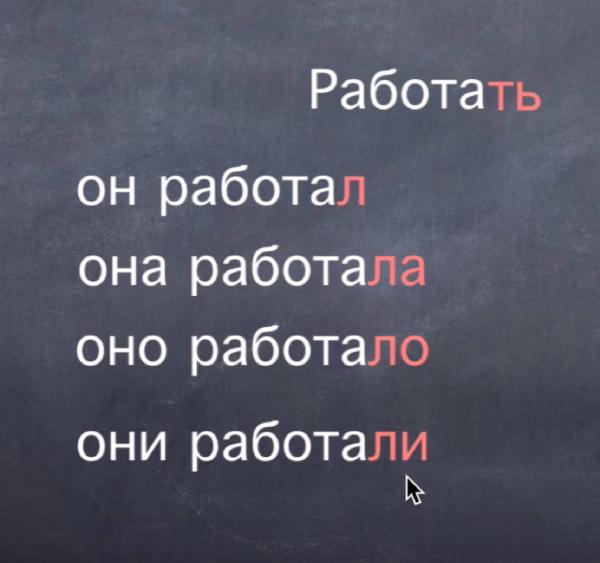

Past Tense

Language

Forming the past tense (прошедшее время) in Russian is very simple. Perhaps the easiest aspect of the entire Russian grammar. The number of variations is limited, and conjugations are not complicated.

First and Second Conjugation

Language

Many Russian verbs end in -ать or -ить. Both categories have their own conjugations. Verbs ending in -ать follow the first or е/ё conjugation; if they end in -ить, then the second or и conjugation applies (exceptions and irregularities aside).

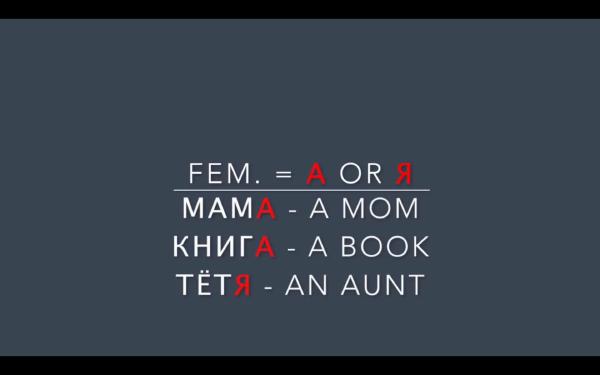

Masculine, Feminine, Neuter

Language

Every noun in Russian is masculine, feminine, or neuter. You always need to know which category it falls into, and usually, that’s not difficult. Words ending in a consonant are masculine, words ending in а or я are feminine, and words ending in о or е are neuter.

Making Sentences

Language

In Russian, you can say a lot with few words. The language is compact, and many sentences are simple. “He is an engineer” is already short, but Russians cut it in half: “He engineer” – that’s all you need to say. The language requires few words but the right ones.