Language

Perfective and imperfective

Language

This often comes as a setback for students of Russian: of (almost) every Russian verb there are two. Which do mean approximately the same thing, but express very different things. So you need to know both, and of both learn the conjugations.

Imperative Mood (Imperative)

Language

Look, this really isn’t difficult. Commands (

orders, mandates) using the

imperative mood. Also known as the imperative, from imperare = to command. With this повелительное наклонение, you can also be polite: it can express a wish, request, or advice.

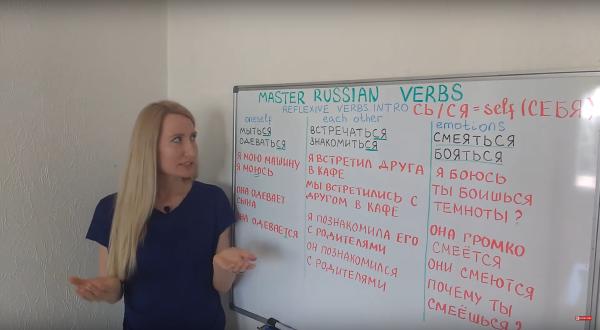

Verbs that relate to oneself are called

reflexive verbs, in English “reflexive verbs,” and in Russian возвратные глаголы. Reflexive verbs often involve a “zich” (oneself) in Dutch; in Russian, this “self” is represented by the suffix -ся at the end of the verb. For example, мыть means to wash, and мыться means to wash oneself (or yourself).

To Be or Not to Be

Language

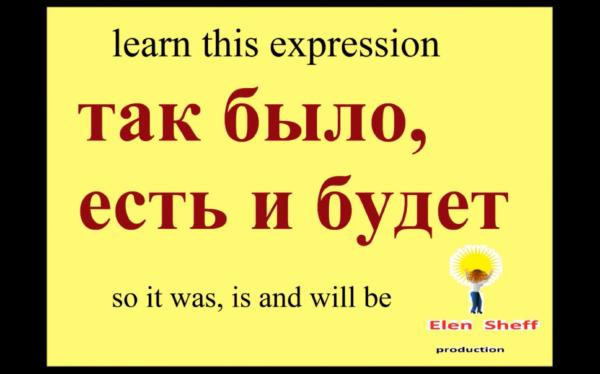

Just like with

the verb “to have”, there’s something odd about the verb “to be” in Russian. It does exist—it’s called быть—but it often goes missing in sentences, unless you’re speaking in the past or future tense. In the present tense, it’s frequently omitted.

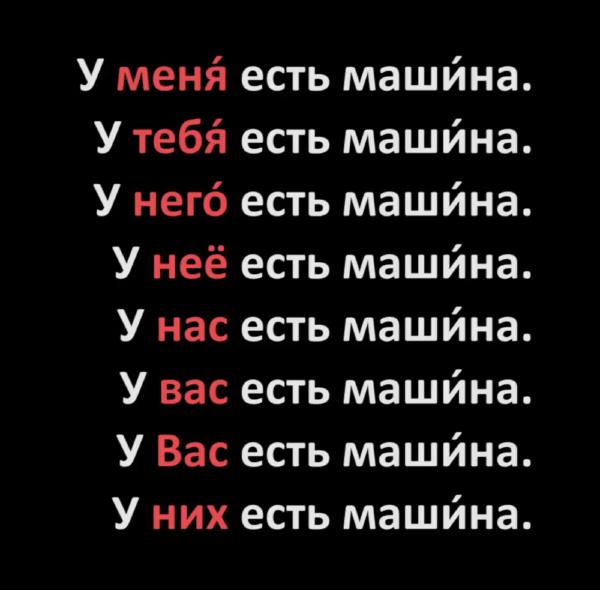

To have, to have, to have

Language

Knowledge you want to have: the verb ‘to have’ technically doesn’t exist in Russian. Of course, there are ways to express possession, but it’s done a bit differently than in many other languages. Somewhat indirectly. Less possessive. Or: a bit more lyrical.

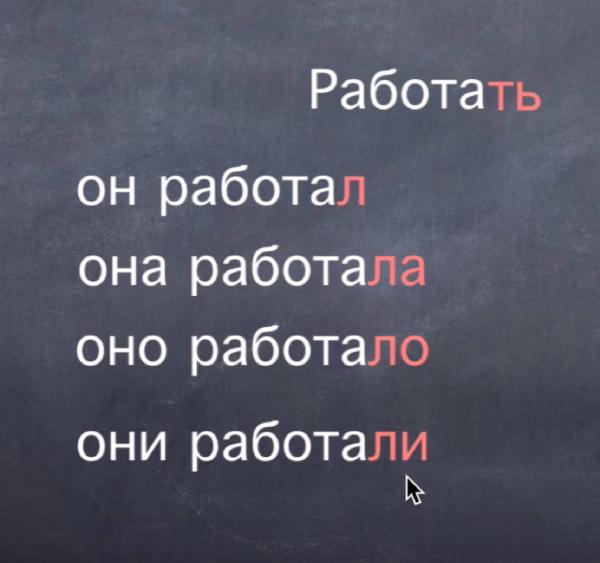

Past Tense

Language

Forming the past tense (прошедшее время) in Russian is very simple. Perhaps the easiest aspect of the entire Russian grammar. The number of variations is limited, and conjugations are not complicated.

First and Second Conjugation

Language

Many Russian verbs end in -ать or -ить. Both categories have their own conjugations. Verbs ending in -ать follow the first or е/ё conjugation; if they end in -ить, then the second or и conjugation applies (exceptions and irregularities aside).