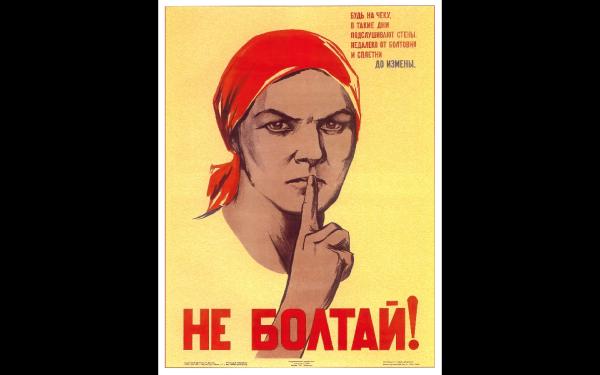

Imperative Mood (Imperative)

Language

Look, this really isn’t difficult. Commands (

orders, mandates) using the

imperative mood. Also known as the imperative, from imperare = to command. With this повелительное наклонение, you can also be polite: it can express a wish, request, or advice.

First, you learn the rules (years of work), then you hear a Russian speaking in real life and don’t understand a single *^&% of it (just an example). Theory is always slightly different from practice, and sometimes the differences are significant.

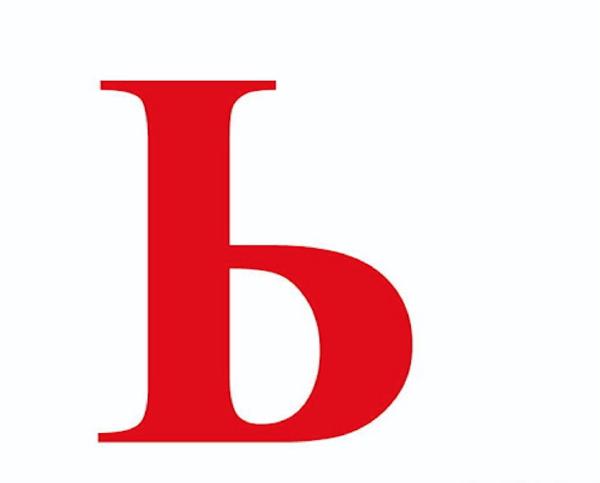

Words ending in ь

Language

As mentioned

here, it’s usually not difficult to determine whether a word is masculine, feminine, or neuter in Russian. It only becomes tricky when a word ends with a soft sign, the мягкий знак or ь, and there are many such words. A useful tip: they are never neuter. As for the rest — masculine or feminine — these rules will guide you.

The nominative case (именительный падеж) is almost a freebie in Russian. The way a word appears in the dictionary is how it appears in the nominative case. ‘Nominative’ comes from

nominare (to name), and in

именительный you may recognize имя, meaning name.

Questions and Question Words

Language

Asking questions in Russian is not difficult. The only difference between a question and a statement can be the tone. Ivan is going to university: Иван идёт в университет. The only thing needed to turn that statement into a question is a questioning tone when speaking, and a question mark when writing or typing.

The letter Ё

Language

The letter ё is the panda of the Russian alphabet. Assuming the panda is teetering on the brink of extinction and in need of special attention. While the panda gets plenty of attention, the letter ё is quietly dying.

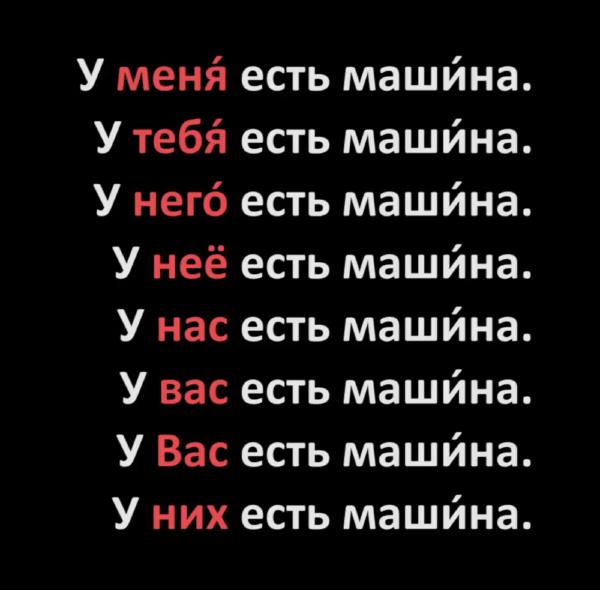

To have, to have, to have

Language

Knowledge you want to have: the verb ‘to have’ technically doesn’t exist in Russian. Of course, there are ways to express possession, but it’s done a bit differently than in many other languages. Somewhat indirectly. Less possessive. Or: a bit more lyrical.