VERBS

Language

Verbs work for those who want to make sentences. There - work and make, there you already have two. And try to make Russian out of that sentence if you if you don’t know работать or делать. So work, also on your vocabulary.

Fifth Case: Instrumental

Language

With “with,” you immediately have the key word for the instrumental case. With a discount, with Katya, with respect, by hand: all instrumental case or творительный падеж. You can do much more with this case; it’s truly a beautiful and useful tool.

Russian Antonyms (антонимы)

Language

Following the introduction on

adjectives, where it was suggested to practice them with opposites or

antonyms (in Russian антонимы). They weren’t provided then and there, but here they are now.

Convenience serves people well. And the linguistic person (whether speaking, typing, swiping, or writing) benefits from shortcuts in the form of abbreviations, truncations, and

acronyms. These are popular in every language because why be long when you can be brief?

Fourth Case: Accusative

Language

The joker in a card game, the knight in chess: if you’re looking for something as quirky among the six cases, you’ll quickly land on the fourth. Rules for the

accusative or винительный падеж are simple, yet (or perhaps because of that) it can easily catch you off guard.

What kind of times do we live in? It’s a question one might ask these days. To get an answer in Russian (or to distract yourself from the times), let’s start by learning the names of the months and days. Here they are gathered together, with a bonus of some etymology and grammar thrown in.

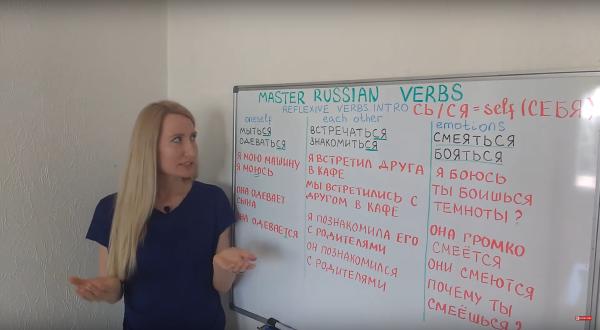

Verbs that relate to oneself are called

reflexive verbs, in English “reflexive verbs,” and in Russian возвратные глаголы. Reflexive verbs often involve a “zich” (oneself) in Dutch; in Russian, this “self” is represented by the suffix -ся at the end of the verb. For example, мыть means to wash, and мыться means to wash oneself (or yourself).

Russian Superstitions

Country

Don’t whistle in the house. Sit down before embarking on a journey. Look in the mirror when you have to return home because you’ve forgotten something. Just a few random rules to bring good fortune or ward off misfortune. Russia has a whole arsenal of such beliefs.

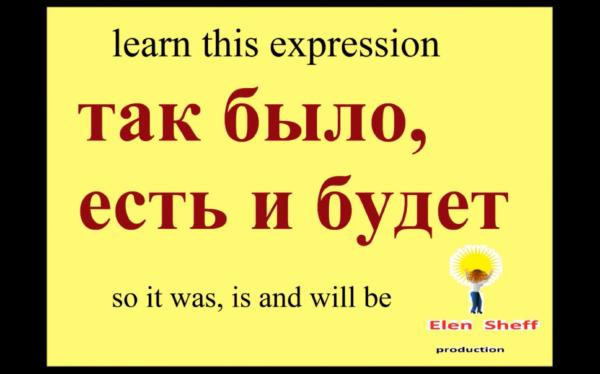

To Be or Not to Be

Language

Just like with

the verb “to have”, there’s something odd about the verb “to be” in Russian. It does exist—it’s called быть—but it often goes missing in sentences, unless you’re speaking in the past or future tense. In the present tense, it’s frequently omitted.

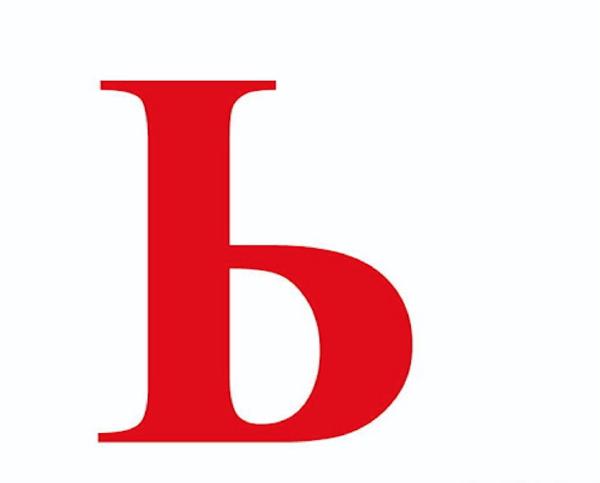

Words ending in ь

Language

As mentioned

here, it’s usually not difficult to determine whether a word is masculine, feminine, or neuter in Russian. It only becomes tricky when a word ends with a soft sign, the мягкий знак or ь, and there are many such words. A useful tip: they are never neuter. As for the rest — masculine or feminine — these rules will guide you.

Questions and Question Words

Language

Asking questions in Russian is not difficult. The only difference between a question and a statement can be the tone. Ivan is going to university: Иван идёт в университет. The only thing needed to turn that statement into a question is a questioning tone when speaking, and a question mark when writing or typing.

Personal Pronouns

Language

You quickly learn or might already know the ‘regular’ forms of the Russian personal pronouns (those in the nominative case). I = я, you = ты, he = он, she = она, it = оно, we = мы, you (formal/plural) = вы, and they = они. These words change depending on the case; however, there are many similarities within these changes.

Learn Russian with Song Lyrics (1)

Language

Song lyrics are compact, memorable, and accessible at all levels. They make studying fun and effective at the same time.