Language

VERBS

Language

Verbs work for those who want to make sentences. There - work and make, there you already have two. And try to make Russian out of that sentence if you if you don’t know работать or делать. So work, also on your vocabulary.

Learning Russian with News

Language

Even with bad news there is good news: there is a lot to learn from it. Russian news articles are excellent teaching material, even for the more advanced student.

SIXTH NOUN: LOCATIVE/PREPOSITIONAL

Language

The sixth noun, in Russian предложный падеж, is for most students the first one they learn. The reason is simple: the sixth grammatical case itself is.

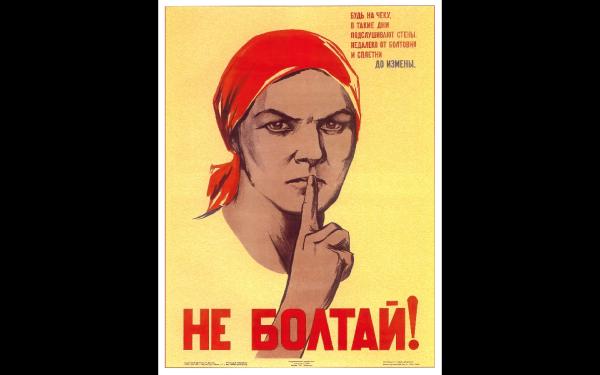

OPERATION WAR

Language

And then it became war. Or should we say began the special military operation. On

February 24 2022 Russian troops entered Ukraine. It was allowed

neither war nor invasion be called, but it was akin to both.

Perfective and imperfective

Language

This often comes as a setback for students of Russian: of (almost) every Russian verb there are two. Which do mean approximately the same thing, but express very different things. So you need to know both, and of both learn the conjugations.

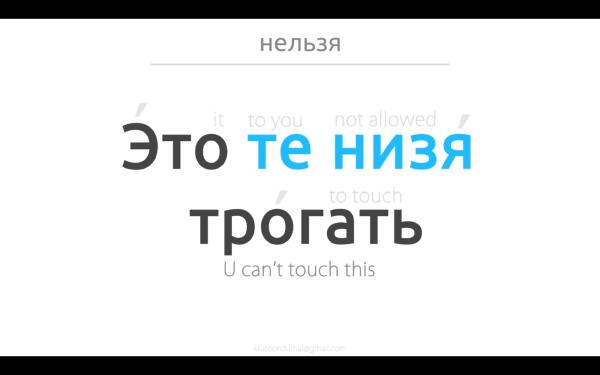

Wrong Cyrillic

Language

Making mistakes in Cyrillic is no big deal. Everyone does. But wrong Cyrillic, that’s the biggest mistake you can make. And the worst thing you can do with that noble Cyrillic can do.

To emphasize one more time that - and why - it is useful and important to to know where the

emphasis added in Russian falls. And how that knowledge helps you, in both the spelling of the word крокодил (crocodile) and the pronunciation of names such as Tolstoy.

Stress (Ударение)

Language

One of the

8 common mistakes every Russian language learner makes according to Russia Beyond (2018). Including a “Word of warning: It takes a VERY long time to get accustomed to the stresses on Russian words At times, you’ll be confronted with a new word and have absolutely no idea how to pronounce it.’ No stress: this is going to help, and will speed things up.

John Cleese – How about Russian?

Language

In a famous scene from

A Fish Called Wanda (1988),

John Cleese (as Archie Leach) speaks some Italian words. “But it’s such an ugly language.” Co-star

Jamie Lee Curtis (as Wanda Gershwitz) has a different opinion. Archie doesn’t see it and suggests something better. “How about… Russian?”

Learn Russian with Interviews

Language

Learn spoken Russian while also getting to know some Russians. From a rocker and a tennis player to Dmitri at the disco and the average Joe. Educational and entertaining: these are the most useful and fun interviews на русском.

Imperative Mood (Imperative)

Language

Look, this really isn’t difficult. Commands (

orders, mandates) using the

imperative mood. Also known as the imperative, from imperare = to command. With this повелительное наклонение, you can also be polite: it can express a wish, request, or advice.

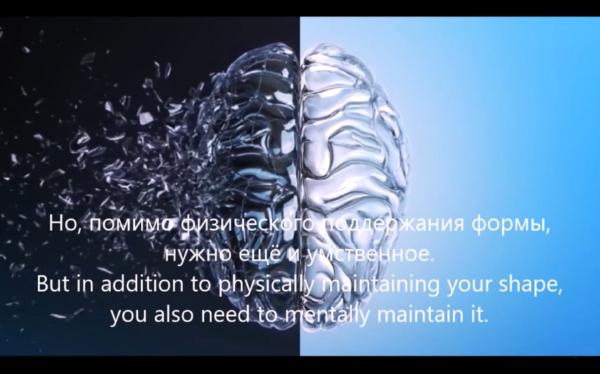

First, you learn the rules (years of work), then you hear a Russian speaking in real life and don’t understand a single *^&% of it (just an example). Theory is always slightly different from practice, and sometimes the differences are significant.

Fifth Case: Instrumental

Language

With “with,” you immediately have the key word for the instrumental case. With a discount, with Katya, with respect, by hand: all instrumental case or творительный падеж. You can do much more with this case; it’s truly a beautiful and useful tool.

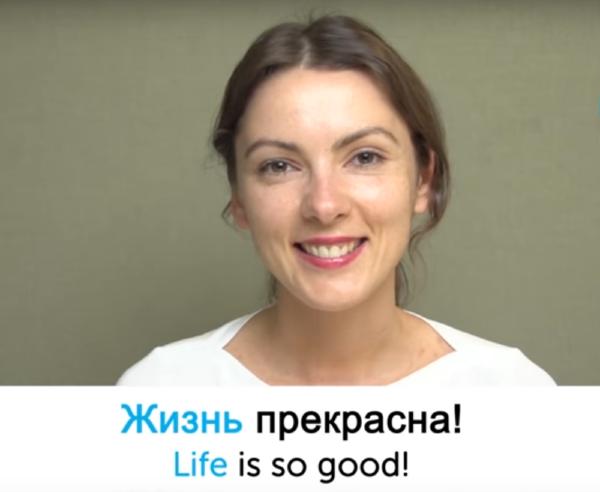

Simply the most beautiful language of all, as stated in

Why Russian. It’s more elegantly and finely formulated, better reflecting the beauty of the Russian language. “Russian has the grandeur of Spanish, the vivacity of French, the strength of German, the gentleness of Italian, and in addition to that, the wealth and brevity of Latin and Greek.”

ш and щ: Spot the Differences

Language

One looks like a “w” with straight lines (like an E that has fallen over), and the other is similar but with a tail or hook. Or something like that. Not only do ш and щ look similar, but their sounds are also close. So close that distinguishing them isn’t easy.

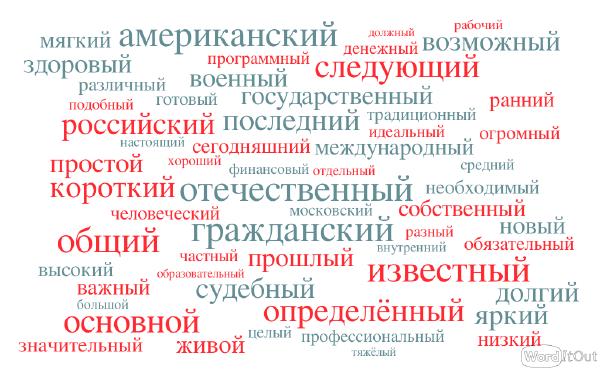

Russian Antonyms (антонимы)

Language

Following the introduction on

adjectives, where it was suggested to practice them with opposites or

antonyms (in Russian антонимы). They weren’t provided then and there, but here they are now.

Russian Adjectives (Прилагательные)

Language

Useful, convenient, interesting: adjectives are everywhere and unavoidable. So it is sensible, rewarding, fascinating, attractive, necessary, etc., to be able to use them in speech and writing. Two things are needed for that.

‘The man we all know: Putin. Does that name actually mean something?’ A question from an interview on FunX with

Ellen Rutten, in celebration of

Russian Language Day (June 6) 2019.

Convenience serves people well. And the linguistic person (whether speaking, typing, swiping, or writing) benefits from shortcuts in the form of abbreviations, truncations, and

acronyms. These are popular in every language because why be long when you can be brief?

Of course, there’s a Russian version of the cat scratching curls off the stairs. And the Russian language wouldn’t be itself if it didn’t have an entire collection of such phrases. Plus, record attempts to say them correctly as fast as possible.

There’s quite a bit of stumbling over Russian words. Whether it’s due to not knowing where the stress falls, strange sounds, or simply because they’re

tongue twisters. This may sound exaggerated, but that’s just what they’re called. Here are difficult and long words that may—or may not—trip up your tongue.

What Does Russian Sound Like?

Language

An unnecessary question, that’s clear from the start. You hear how Russian sounds everywhere here, and you’ll come to an answer yourself if you haven’t already. Still, it might be interesting to hear how others perceive the sound of Russian. Also, to see what kind of reputation the language enjoys (or endures).

Russian Ordinal Numbers

Language

After covering the basic

numbers or

cardinal numbers, here’s the second part:

ordinal numbers, like first and second. In English, they’re called ordinal numbers, and in Russian, they are порядковые числительные (stress on the second syllable both times). Ordinal numbers are usually easy to derive from the cardinal number – although words like “first” and “second” are exceptions right from the start.

Fourth Case: Accusative

Language

The joker in a card game, the knight in chess: if you’re looking for something as quirky among the six cases, you’ll quickly land on the fourth. Rules for the

accusative or винительный падеж are simple, yet (or perhaps because of that) it can easily catch you off guard.

Russians and English

Language

Another reason to learn Russian (see

Why Learn Russian) is that Russians don’t speak English. Or rather, not everyone does. And among those who do, not all are equally fluent. How come? Let’s explore. With insights from the Russians themselves at the end.

What kind of times do we live in? It’s a question one might ask these days. To get an answer in Russian (or to distract yourself from the times), let’s start by learning the names of the months and days. Here they are gathered together, with a bonus of some etymology and grammar thrown in.

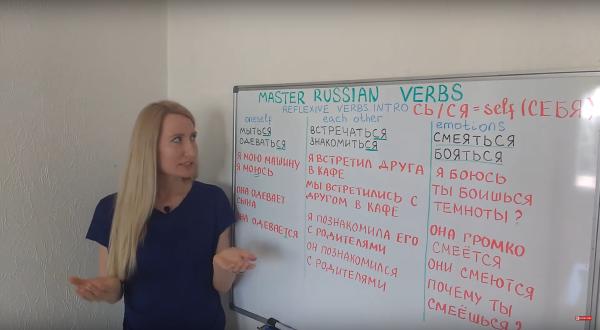

Verbs that relate to oneself are called

reflexive verbs, in English “reflexive verbs,” and in Russian возвратные глаголы. Reflexive verbs often involve a “zich” (oneself) in Dutch; in Russian, this “self” is represented by the suffix -ся at the end of the verb. For example, мыть means to wash, and мыться means to wash oneself (or yourself).

Зелёная лампа (The Green Lamp) is a short story from 1930 by Aleksandr Grin (1880-1932), the surname being an abbreviation. Regarding Aleksandr Grinevski (Russian: Александр Гриневский), Wikipedia offers a real recommendation: “His stories mainly revolve around the sea, adventures, and love.”

How Difficult Is Russian?

Language

A frequently asked question that’s not so easy to answer. There are certainly degrees of difficulty (see

How long it takes to learn Russian; more at the bottom), but what’s a breeze for one person can be a challenge for another. Some can run a marathon with ease, while others struggle to bike even half the distance.

Learn Russian with Films (1)

Language

With Russian films, you can learn the language and practice listening while lounging on the couch with chips and soda (just to paint a scenario). Learning becomes enjoyable, and watching films becomes productive—almost the perfect combination.

The letter ы

Language

It looks like two letters but has an indescribable sound. The 29th letter of the Russian alphabet is quite unique and often causes problems with pronunciation. We are talking about the letter ы, a sound not found in many other languages (except perhaps Turkish). As such, it takes some effort to pronounce it correctly.

Third Case: Dative

Language

The

dative case in Russian is called дательный падеж. The name itself gives you a clue when to use it. In дательный, you find дать, which means “to give” (also давать—see

here for conjugations). This originates from Latin, where dare means “to give” and datum means “given.” In Russian, when something is given, it’s done in the dative case, just like in many other languages.

To Be or Not to Be

Language

Just like with

the verb “to have”, there’s something odd about the verb “to be” in Russian. It does exist—it’s called быть—but it often goes missing in sentences, unless you’re speaking in the past or future tense. In the present tense, it’s frequently omitted.

Russian Slang

Language

A definition of slang is hard to pin down. But why try when others have already done it? According to

Wikipedia, slang refers to “registers of language usage that are either reserved for a social group or considered ‘vulgar,’ meaning substandard language.”

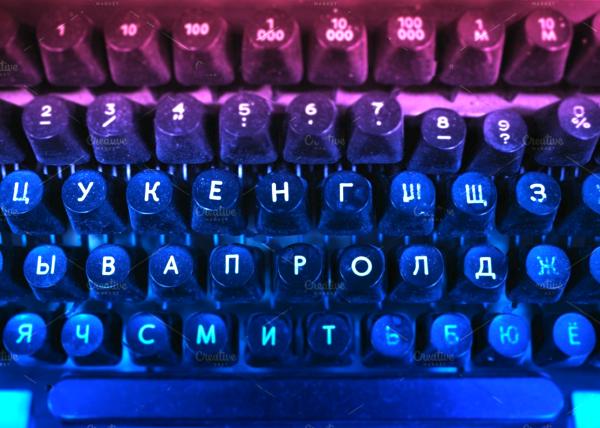

Russian Keyboard

Language

Typing Russian letters and characters isn’t easy at first, but it’s definitely worth the effort. It opens up a whole new world—or at least a lot of the internet. It’s also necessary if you want to do anything in Russian.

Your first goal is going to be to get Russian on your computer (College Russian, 2018, 7 m, with more tips to find your way online).

Is Grammar Unnecessary?

Language

This might sound like music to many ears: learning Russian without grammar. Is this a case of ‘too good to be true,’ or is it really possible? The advice of

Benjamin Rich (Bald and Bankrupt on YouTube) is clear. Forget grammar. In fact, (from the description under the video embedded here), ‘throw away the grammar books and you’ll make massive progress very quickly.’

A Russian name consists of three parts: a first name (имя), a patronymic or father’s name (отчество), and a last or family name (фамилия). The abbreviation Ф.И.О. (фамилия, имя, отчество) is well-known to Russians and appears on their passports, driver’s licenses, and related documents.

Words ending in ь

Language

As mentioned

here, it’s usually not difficult to determine whether a word is masculine, feminine, or neuter in Russian. It only becomes tricky when a word ends with a soft sign, the мягкий знак or ь, and there are many such words. A useful tip: they are never neuter. As for the rest — masculine or feminine — these rules will guide you.

Learning Russian during the pandemic

Language

For Russian hobbyists and students, the pandemic (is? was? will be?) not all bad. In many cases, some extra time became available, and what better way to spend it than learning русский.

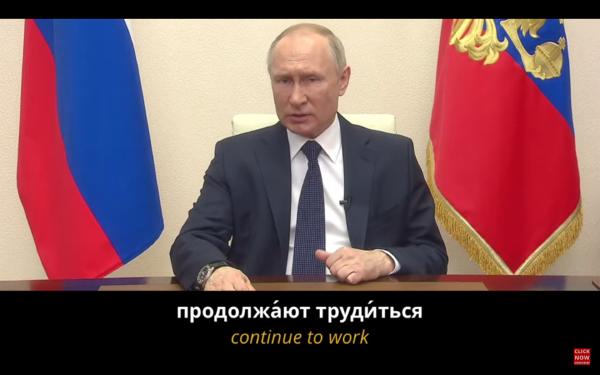

From earlier (2017) and corona-free, here’s an analysis by Anna Cher (Russian from the Heart) of a short excerpt from a TV interview. Putin talks about social media and the common practice of operating under a pseudonym.

Whatever your opinion may be of Russia’s president, his language is excellent material for learning. He expresses himself clearly, but with sentences that are not simple or impoverished — something not all presidents manage, even in their own language. While the language isn’t always easy and may not be ideal for beginners, there are subtitles and explanations available, and it’s about more than just language alone.

Second Case: Genitive

Language

As easy as it was with the

first case, it becomes that much more complicated with the second. The genitive or родительный падеж is challenging in several areas. It is the most used and versatile, but also the most complex.

The nominative case (именительный падеж) is almost a freebie in Russian. The way a word appears in the dictionary is how it appears in the nominative case. ‘Nominative’ comes from

nominare (to name), and in

именительный you may recognize имя, meaning name.

Questions and Question Words

Language

Asking questions in Russian is not difficult. The only difference between a question and a statement can be the tone. Ivan is going to university: Иван идёт в университет. The only thing needed to turn that statement into a question is a questioning tone when speaking, and a question mark when writing or typing.

Personal Pronouns

Language

You quickly learn or might already know the ‘regular’ forms of the Russian personal pronouns (those in the nominative case). I = я, you = ты, he = он, she = она, it = оно, we = мы, you (formal/plural) = вы, and they = они. These words change depending on the case; however, there are many similarities within these changes.

The letter Ё

Language

The letter ё is the panda of the Russian alphabet. Assuming the panda is teetering on the brink of extinction and in need of special attention. While the panda gets plenty of attention, the letter ё is quietly dying.

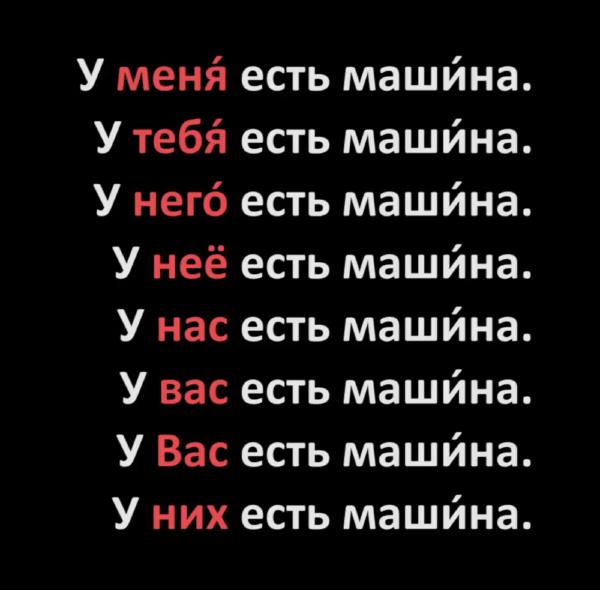

To have, to have, to have

Language

Knowledge you want to have: the verb ‘to have’ technically doesn’t exist in Russian. Of course, there are ways to express possession, but it’s done a bit differently than in many other languages. Somewhat indirectly. Less possessive. Or: a bit more lyrical.

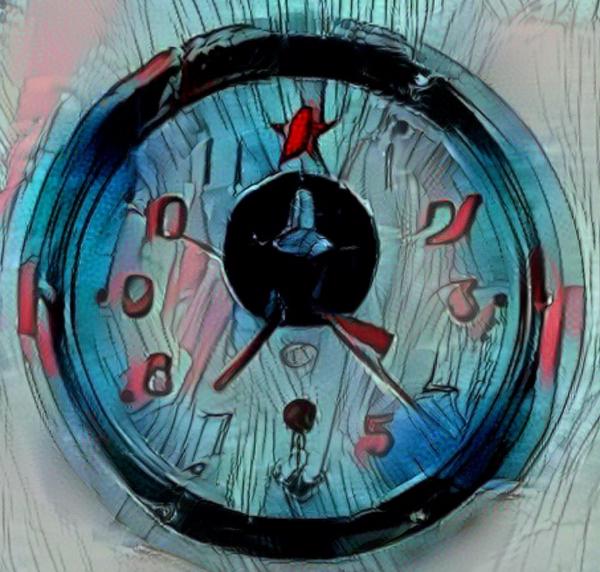

Telling Time in Russian

Language

When Russians tell time, they look ahead. In the first half-hour, they are already on their way to the next, and in the second, they tell you how far it is to the next hour. To understand this and be able to do it yourself, there are a few things you need to know. Here are the most important ones.

Anastasia Semina (

Russian with Anastasia) created a series called Short Stories in Russian with Subtitles. YouTube has a

Playlist.

In particular, parts 1 and 2 are recommended. Anastasia in the library with Tolstoy and a lamp. Russian text with English subtitles on screen (2017).

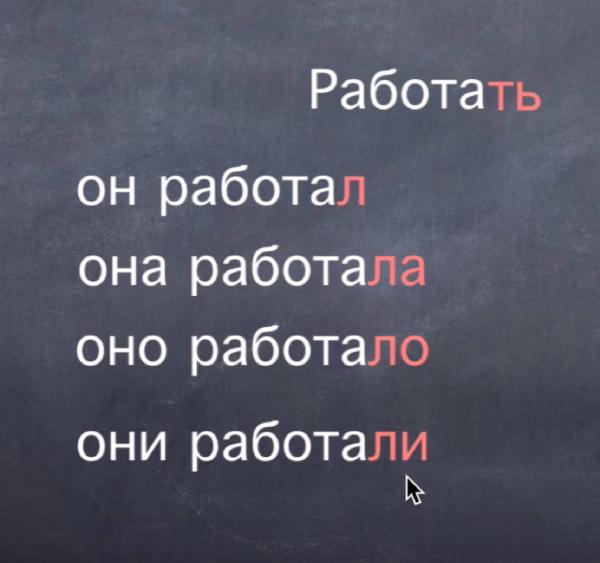

Past Tense

Language

Forming the past tense (прошедшее время) in Russian is very simple. Perhaps the easiest aspect of the entire Russian grammar. The number of variations is limited, and conjugations are not complicated.

First and Second Conjugation

Language

Many Russian verbs end in -ать or -ить. Both categories have their own conjugations. Verbs ending in -ать follow the first or е/ё conjugation; if they end in -ить, then the second or и conjugation applies (exceptions and irregularities aside).

Six Cases

Language

Cases are often seen as the ‘Ghost’ of the Russian language. Like the

white rabbit in

Monty Python and the Holy Grail: ‘Look, that rabbit’s got a vicious streak a mile wide, it’s a killer!’ In this case, it’s a six-headed monster.

Counting and Numbers

Language

Numbers in Russian can already be a puzzle when you’re counting from 1 to 10. The words for 4 (четыре) and 5 (пять) don’t resemble anything you’re familiar with, восемь (8) is also strange, and 9 (девять) and 10 (десять) sound alike.

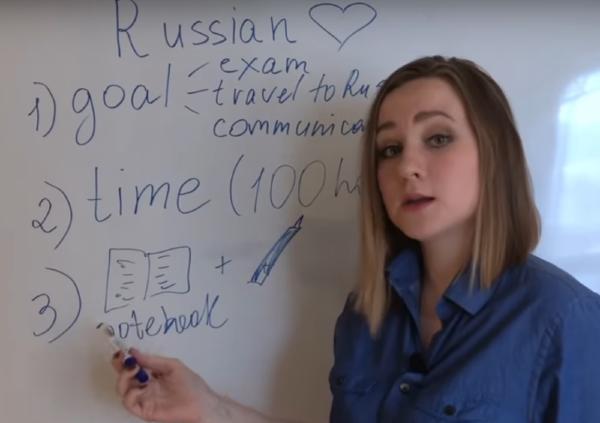

How Long It Takes to Learn Russian

Language

Anyone starting something wants to know when they’ll finish. How long does it take to understand, read, and speak Russian? How much time does it take to learn the language well? Как долго (how long), сколько (how much)?

Learn Russian with Song Lyrics (1)

Language

Song lyrics are compact, memorable, and accessible at all levels. They make studying fun and effective at the same time.

Why Learn Russian?

Language

There are many reasons to (want to, start, or continue) learning Russian. It’s the language of the world’s largest country, the biggest language in Europe, and it’s useful in many countries outside of Russia too. And perhaps the best reason to learn Russian: simply the most beautiful language of all.

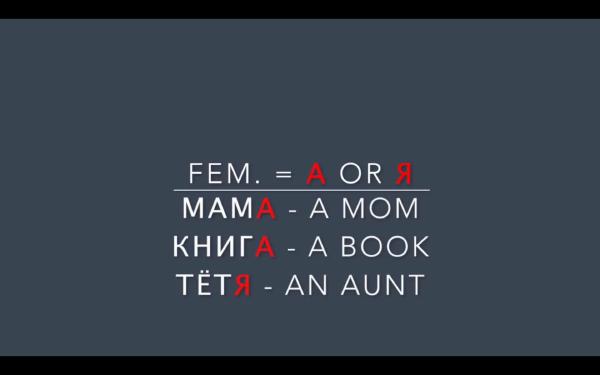

Masculine, Feminine, Neuter

Language

Every noun in Russian is masculine, feminine, or neuter. You always need to know which category it falls into, and usually, that’s not difficult. Words ending in a consonant are masculine, words ending in а or я are feminine, and words ending in о or е are neuter.

Sentences for Beginners

Language

For beginners, there are plenty of sentences to see, listen to, and repeat so that you can quickly make your own beautiful sentences. Useful for this purpose is the video below from

RussianPod101, featuring words like потом (then), но (but), тем временем (meanwhile), and seven more.

Making Sentences

Language

In Russian, you can say a lot with few words. The language is compact, and many sentences are simple. “He is an engineer” is already short, but Russians cut it in half: “He engineer” – that’s all you need to say. The language requires few words but the right ones.

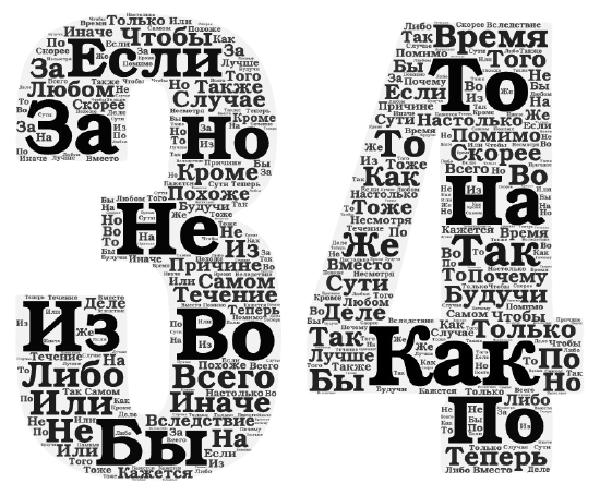

Sentence Structures with Max

Language

From

Russian with Max, here are the 34 самые популярные конструкции русского языка (the 34 most popular sentence structures of the Russian language). Useful words and conjunctions, each with two examples, read aloud (by Max) at two different speeds. With English translation; summary (with Dutch translation) below the video.

Gluing Sounds

Language

Russian is a phonetic language. The way you pronounce words is how you write them. The way they are written tells you how to pronounce them. Each letter has its own sound and generally keeps it. Unlike Dutch and English, Russian is quite consistent in this regard.

(Image © Gummbah)

(Image © Gummbah)

Vocabulary

Language

A short poem (called ‘Woordenschat’ – Vocabulary) by Jaap van Lakerveld goes like this:

A man whose small vocabulary

I estimate to be six words

says to the woman who loves him

when she asks how he feels about her

‘I don’t have the words, my dear’

A man whose small vocabulary

I estimate to be six words

says to the woman who loves him

when she asks how he feels about her

‘I don’t have the words, my dear’

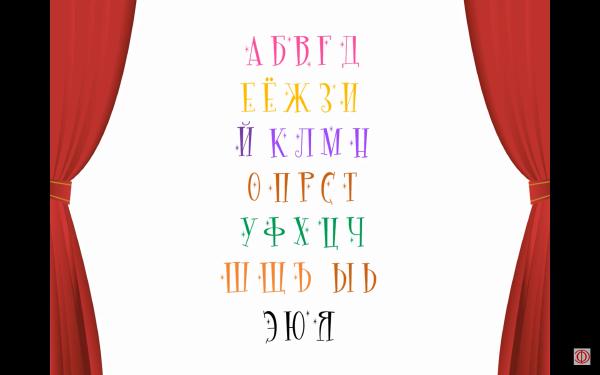

Alphabet Music

Language

If you’re tired of the ABC videos but still haven’t mastered the алфавит (alphabet), you can listen to songs that Russian children sing to get it into their heads. Useful for remembering the order of the 33 буквы (letters), though you may feel for them.

Cyrillic

Language

Cyril and

Methodius, brothers and Christian monks, are at the foundation of the Russian script. It is called

Cyrillic because Cyril invented it, in the primitive form of the

Glagolitic alphabet, which was revised and simplified after his death. Cyril and Methodius came from

Thessalonica (Greece) and were missionaries: the script was meant to translate the Bible and spread the faith.

A Piece of Cake: Russian Alphabet

Language

Learning Russian begins with that fascinating alphabet. 33 characters, just 7 more than in our ABC, so how hard can it be? Find out for yourself, of course. Try apps, for example: plenty of options on Google Play and Apple App Store, often for free. Or by watching and listening to clips – also for free. The second language is usually English.